5th Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, Cambodia

May 5-19, 1970

199th Infantry Brigade

"Light Swift Accurate"

12infrgt.gif

The 1st Cavalry Division's Operational Report for that period gives a broad outline of the swift moving events, to include the dates and events involving the 5th Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment who were under the operational control of the 1st Cavalry Division's 2nd Brigade. The 5th Battalion, 12th Infantry had for nearly six months operated around Firebase Libby and Gladys in Long Khanh Province. Daily, they worked in extreme heat, heavy jungle, and monsoon rains, searching for the 274th Viet Cong Main Force Regiment and the 33rd NVA Regiment - with occasional success resulting in 2 to 3 enemy KIA:

../ds/SpencerAx01k.jpg

Cambodian events for the 5th Battalion of the 12th Infantry Regiment, 199th Light Infantry Brigade (LIB) (Separate) began during the morning of 5 May, 1970 when the 5-12th Infantry was released by the 199th to the operational control of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, effective at 1840 hours. The battalion relocated to Phouc Long Province, near Song Be, in South Vietnam to operate and provide defense for FSB Buttons, the headquarters of the Cav's 2nd Brigade.

Below shows SGT Arlie Spencer with men from his unit; date, location, and men unknown. SGT Spencer is on far left of photo.

../ds/SpencerAx01e.jpg

From 5 May until 12 May, the "Redcatchers" 12th Infantry Regiment worked in their new area of operations, seeking the locations of the enemy, again encountering light enemy resistance. Then they went into Cambodia from 12 May until 25 June 1970.

On 9 May, the battalion was extracted from their field locations and combat assaulted into FSB Snuffy at BU GIA MAP, taking 3 hours to complete the move. They deployed to conduct operations to interdict enemy eastward movement from their Base Area 351 and along the JOLLEY Trail.

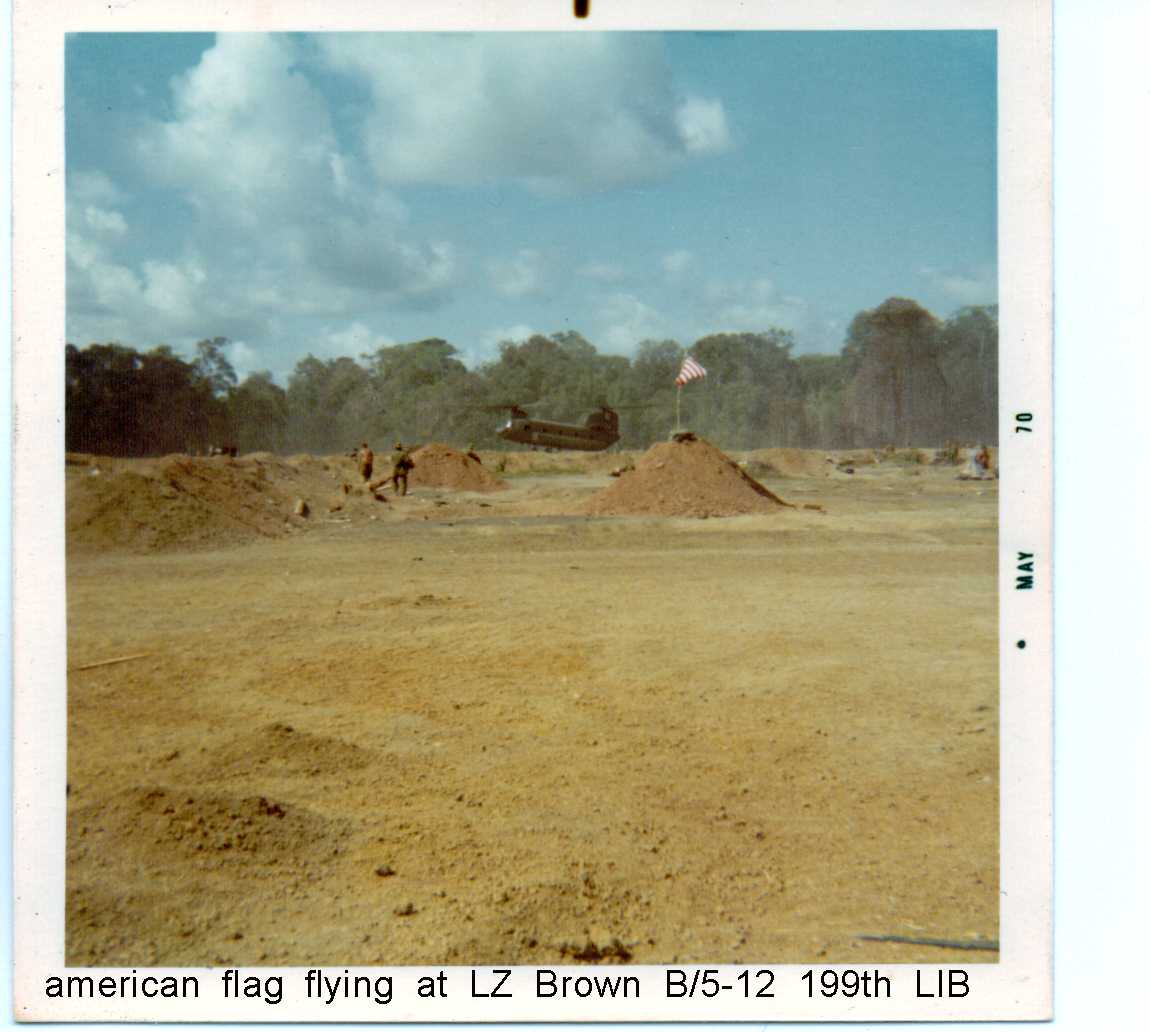

On 12 May, Companies B and C, 5-12th Infantry were released from their Battalion control to be OPCON with Task Force 2-12, led by the 2nd Battalion, 12th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division. The next day, the Battalion moved from FSB Snuffy and establised a command post at FSB Brown, Cambodia. B & C Companies, 5/12th Infantry, part of TF 2-12, had occupied FSB Brown the night before.

One of the Alpha Company men, a rifleman with the company since February described Alpha Company's first day in Cambodia. "On our first day, all the line units from the battalion were sent several klicks from FSB Brown on Reconnaissance in Force (RIF) missions. The terrain and jungle here was absolutely terrible. The jungle foliage, versus back in Vietnam, was much, much thicker. It was almost impenetrable in most places and there was bamboo everywhere. The bamboo grew in super-thick stands well over 8 to 10 feet. The place was also infested by huge, black leeches that sought us out everywhere we went. Combined with these factors with the NVA soldiers we were fighting, it made for a very unhealthy place." (Information used with permission of Robbie Gouge, author of "Raiding the Sanctuary".)

At 0215 hours, 13 May, 40 to 50 individuals were observed movng toward the FSB. Supporting 12th Infantry Regiment's companies engaged the enemy with organic weapons supported by artillery, Aerial Rocket Artillery (ARA), Shadow, Nighthawk, tactical air, a flare ship and Blind Bat (C-130 air support). They received small arms, automatic weapons, and B-40 rocket fire in return. The battle ensued for 2 and a half hours, breaking at 0545 hours. Enemy losses were 50 KIA, 4 rocket launcers, 11 SKS rifles, 17 AK-47s, 2 K54 pistols, a 6mm mortar captured. The US lost one soldier killed in action and 4 wounded in action. Later in the day, Task Force 2-12 was dissolved and became TF 5-12th under command of the 5th Battalion, 12th Infantry and now included Troop I, 3rd Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment. The soldier killed on FSB Brown during the early morning fight on 13 May 1970 was:

SP4 Richard Gill DeSillier, A Company, Pawcatuck, Connecticut

On 14 May, men from Alpha Company were busting brush trying to find enemy storage depots and cache sites. Late in the morning, they were being shadowed by an OV-10 Bronco plane flown by 1LT Patrick W. Kellogg and an artillery spotter from the 184th Aviation Company, 1st Aviation Brigade.

CPT Kellogg was well-known among the company commanders and platoon leaders in 5-12 as he had worked with them before in Vietnam, calling in timely and accurate air and artillery strikes for various units in contact.

As Kellogg was making another pass over Alpha buzzing the treetops looking for anything out of place or suspicious, his plane was suddenly cut in two by a hidden NVA .51 caliber heavy machine gun. Kellogg was killed instantly. (This was possibly the same enemy machine gun that had riddled LZ Brown with bullets during the firefight two nights before. The next day, Sniper Team B from Echo Company, 5-12th Infantry found what was left of the aircraft, along with the log book and confirmed that both Kellogg and the spotter were killed by enemy small arms) (Information used with permission of Robbie Gouge, author of "Raiding the Sanctuary"). The two men killed (data from Coffelt Database and 184th Recon Airplane Company History, states the men who were killed on 15 May) in their O-1 Birddog aircraft by enemy fire while flying over Khet Mondul Kiri Province, Cambodia were:

1LT Peter Patrick W Kellogg, Seattle, Washington (Pilot)

SP4 Kenneth Eugene Smith, Woodville, Wisconsin, (Spotter)

219th Military Intelligence Detachment, II Field Force.

Also on the morning of May 15, 1970, while a Command and Control Helicopter from Charlie Company, 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion (AHB) was on the ground at YU 067398 to drop off reporters, it was attacked by 8 NVA with rifles and B-40 rockets. The aircraft went up in flames as troops from the 5-12th Infantry Regiment had been in contact to secure the area. Casualties were 1 US KIA and 3 US WIA. The men killed were:

SFC Arnold Lee Robbins, Salamanca, New York

8th Engineers, 1st Cavalry Division, killed outright,

SP4 John Richard Stinn, Panama, Iowa, (Crewman)

229th AHB, 1st Cavalry Division, wounded, evacuated, died later.

SGT Melvin Ray Thomas, Ada Michigan,

8th Engineers, 1st Cavalry Division, wounded, evacuated, died later

The men of Bravo Company walked into an ambush late in the afternoon in what they thought was an abandoned enemy base camp. SGT Pete Spencer lost his life during this event, and several were wounded in the firefight which lasted most of the night.

No 'official' unit information on the encounter was documented in the Cambodia report by the 1st Cavalry Division, nor in the documents of the 12th Infantry Regiment. The story was told by the men who lived it and can be found in detail in the book "Raiding the Sanctuary". Exerpts from the book used with permission of the author.

By 1400 hours, Bravo Company, with the daily monsoon rains soaking the already exhausted Redcatchers to the bone, had moved out of the contact area, once again jungle pounding through the extremely thick Cambodian countryside. The company was paralleling the same river where the chopper had gone down, two hundred meters or so northeast of FSB Brown.

When the 2nd and 3rd Platoons finished crossing over [rope bridge into enemy base camp], CPT Lee formed the company into a defensive perimeter. From the outset, it was apparent that the basecamp was huge and much too large for one regular line infantry company to handle.

Allen Thomas of the 2nd Platoon states that, "This NVA compound was huge. After we formed a perimeter, each platoon started taking out short reconnaissance patrols to find out just what the extent of the camp was and see if there were any NVA around..." The patrol from the 3rd Platoon, which went in the opposite direction of Thomas's, was led by Terry Braun and Arlie "Pete" Spencer.

Braun remembers, "CPT Lee summoned Pete Spencer and me to meet with him. He told us to take a few men and run a short recon patrol about 75 to 100 meters outside of the perimeter we had just set up. He suggested that we stay off any trails and then report back to him when we had gone a sufficient distance. We took along our RTO's, three M60 machine gun teams and a pointman. We tried to stay off the trails, but the thick bamboo bordering the camp kept forcing us back onto the well-beaten paths. When we had gone approximately 75 meters, we came upon a gully that ran next to the river we were paralleling. I stopped and told Pete, 'That's it. 75 meters. Let's go back.' Pete quickly shot back, 'The Captain said 75 to 100 meters.' He then pointed out fresh sandal tracks. You could actually see where the NVA wearing them had hurriedly slid down the embankment into the gully and back up the other side. The gully wasn't that large of a physical feature. It was probably an 8 to 12 foot drop down a very slippery and muddy trail. It ran about 50 to 80 feet to where the trail went back up a hill to the other side and it was probably a little less than that to the hill that surrounded the gully to our right. The river was to our left."

Braun immediately called up CPT Lee and told him the situation and about the tracks. Loaning SGT Spencer his M60 team consisting of Ken Burmeister and Vaughn Bartley, he then told CPT Lee that Spencer was going to probe a little further.

Braun continues. "Walter Case, who just hours ago had helped to rescue the burning crew of the Huey that was shot down, was pleading with the patrol to not enter the gully. He somehow knew that it was a bad omen. I was the seventh one to descend the hill and enter into it. My RTO would have been the eighth and final one, but as I was going down the hill, Pete Spencer was slipping and sliding in the mud trying to get up to the top on the other side. While watching him, I took a quick glance at the area around me. I immediately noticed an enemy bunker pointing in our direction from across the river. I put my hand up to stop the squad from going any further and halted my RTO, who was himself halfway down the trail leading into the gulley. Just at that moment, at approximately 1650 hours, there were two ear-splitting bursts of automatic weapons fire. There is a distinct difference in sound between and M16 rifle and an AK-47. The AK is much louder and makes more of a cracking noise when fired. The M16 looks like a toy and it has a milder popping sound. These bursts of fire were from an M16 and my first thought was that Pete Spencer had crawled up the other side, seen some enemy soldiers and fired at them. ..."

Spencer had made it up to the opposite side of the gully when the firing began. However, it was not from his weapon or from anyone else's in the patrol. An NVA soldier, using an M16, had shot Spencer through the back of the head when he had appeared at the top of the gulley. He never knew what hit him. Seconds before the shots were fired, Spencer turned around to help Ron Scarbrough, who was carrying another M60 machine gun. The rounds that killed Spencer also hit Scarbrough, seriously wounding him in the back and buttocks.

After the two bursts of fire, there was total silence in the gulley for several heart-pounding minutes. The men at the bottom of the ditch were sure that the enemy were fleeing as they had done many times prior to artillery fire crashing after them. That was not the case on May 15th.

Within minutes, the 1st and 2nd Platoons at the company perimeter, 100 yards or so back from the 3rd Platoon, began receiving heavy and accurate AK-47, RPD and RPG fire at a distance of less than 75 meters. At least nine grunts were wounded in the opening fusillade. Bravo Company was strung out and under heavy enemy fire. There was nothing for the men to do but pray and spray the jungle in front of them with their weapons on full-automatic. Serpent A1, the O-1 observation plane buzzing over the contact was immediately driven off by a string of accurate ground to air machine gun fire. "

The battle continued for hours more with the Company finally consolidating their platoons but they spent the night repelling probes by the NVA who were trying to find a weak spot. The firing would suddenly start up again, reach a crescendo after a few minutes and then die back down.

The next morning, an overland attempt by Bravo Company of the 1st Cav's, 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry was made earlier that morning to reach the survivors of Bravo Company at the basecamp. After two hours of hacking and tromping through the bush, they were themselves ambushed a couple of kilometers from FSB Brown and suffered one KIA and seven WIA right from the start. Bravo 2-12 immediately pulled back. It was the Sheridan's and ACAV's from I Troop, 3rd Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry who finally got them out of the bunker complex where they continued to fight all day until 1630 hours.

Several of the men from 3rd Platoon, including the platoon leader, raced back into the gully to retrieve the body of Pete Spencer. They made it back just as the column was leaving the area. But the column was ambushed about 1 klick from FSB Brown and another 8 men were wounded in action before they finally reached the relative safety of FSB Brown.

SGT Arlie 'Pete' Spencer was posthumously awarded the Silver Star for his heroic actions of May 15, 1970. The names of the men from 5th Battalion, 12th Infantry who were killed in action in Cambodia were:

SP4 Donald Gene Busse, Pontiac, Michigan

PFC Charles Castulo Cisneros, Cerro, New Mexico

CPL Raul De Jesus-Rosa, Juncos, Puerto Rico

SP4 Richard Gill Desillier, Pawcatuck, Connecticut

SGT Dannie Lee Hawkins, Hanceville, Alabama

SGT Michael William Notermann, Victoria, Minnesota

CPL Allen Eugene Oatney, Waterville, Kansas

SGT Jon William Rich, Menominee, Michigan

SGT Warren Lee Scanlan, Exmore, Virginia

SGT Arlie "Pete" Spencer, Westland, Michigan

PFC Ronald Richard Stewart, Glenrock, Wyoming

SP4 Robert John Urbassik, Cleveland, Ohio

PFC Johnny Mack Watson, Mobile, Alabama /li>

Visit the following links to read more on the 5th Battalion, 12th Infantry, in Cambodia

Visit a 'Redcatchers' website for more details

From Terry Braun's email of July 1, 2013. "The helicopter exploded (was shot down) the morning of May 15th. It brought a camera crew from CBS in to film our unit. Pete was killed in the afternoon of May 15th, at least 6 hours after the helicopter was shot down."

"I was in the entire 26 hour firefight on May 15th to May 16th in the NVA Bunker Complex and we never saw a helicopter explode (except that morning). We had a soldier dropped from a Medevac as we were dusting him off (Vaughn Bartley, Pontiac, Michigan) but he survived and went to Fort Knox then Valley Forge for the next 56 weeks for multiple surgeries. My machine gunner, Ken Burmeister and I went to visit him at Christmas, the following year."

"As far as the chopper that was shot down the morning of May 15, 1970, I can personally confirm 2 KIAs and 2 severely wounded (burned all over their bodies) that we dusted off but I was later told those 2 also died. The CBS crew left on that chopper and missed the May 15th -16th firefight."

"I have included my versions of May 12-13 and May 15-16 to help clarify those events (Read them here). "Again, thank you so much for doing this for all the soldiers and families, it is greatly appreciated. I think of Arlie "Pete" Spencer everyday."

- - - Terry Braun

From Robert Gouge June 24, 2013 email: "I am glad that the information will be helpful. Once again, please use anything and everything at your leisure."

"I have also attached the full manuscript to "Raiding the Sanctuary" for you to use as well [Read Chapter 2 of his manuscript here]. There is quite a bit of information in there that you may be able to use for other personnel and incidents during the Cambodian Incursion."

"Please contact me at any time if you have any further questions or concerns. I'd be happy to help out in any way."

- - - Robby Gouge

Contact Us Copyright© 1997-2013 www.VirtualWall.org, Ltd ®(TM) Last update 06/30/2013